If your idea of how fish feed on the reef is ferocious hunters swooping in to grab other fishy prey, you’re very unlikely to see that on most dives. But the 28,000 species of bony fishes in the world’s oceans make their livings in a myriad of ways – and they’re doing it all around you.

IF YOU’RE SURPRISED AT HOW LITTLE FISH-ON-FISH FEEDING ACTION YOU ACTUALLY SEE WHILE YOU’RE UNDERWATER, a major reason is that you’re probably diving at the wrong times.

The fishes that do prey on other fishes – “piscivores” – mostly do so during the twilight hours at dusk and dawn, when the environment of changing light gives them an edge on targeting fishy prey. Very little piscatorial predation takes place during the daytime, when most divers dive, or once darkness has settled in solidly, when most night dives take place.

AND ANOTHER THING:

Whatever their culinary styles, nearly all bony fishes share one common approach to food: They vacuum it in by simply opening their mouths. When they open their mouths they create a negative pressure that draws in water and anything that happens to be in it. As they close their jaws, the ingested water is flushed out through the gills.

A fishy predator’s consumption of a fishy prey happens at lightning speed. It’s so fast, you may be watching while it happens and never see it.

FISH BASICS ON POSEIDON’S WEB – EXPLAIN THE REEF!

- How Fish Breathe: Ram Ventilation, Buccal Pumping

- How Fish Sleep: By Resting, Snoozing & Totally Zonking Out

- Fish Buoyancy – How Our Finny Friends Stay Neutral (Unless They Don’t)

- Words: Osteichthyes vs. Chondrichthyes, Bony vs. Cartilaginous

AND ANOTHER: MOST OF THEM ARE FEEDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

You may not see much in the way of fish-on-fish predation during daylight hours, but many fishes on the reef are busy through the day consuming oceanic delicacies before your eyes – as herbivores, planktivores and invertebrate-dining carnivores.

VIDEO SIDEBAR: BOTTOMFEEDERS

For lots of fish and other reef denizens, “bottom-feeding” is a productive way of life. We may see a sandy seafloor as something like an empty desert. But actually, the sand is crammed with life – worms, crabs, crustaceans like copepods, clams and other mollusks, bacteria and decaying organic matter. And lots of fishes go after them – by “fracking” with jets of water, stirring them out by flapping fins, feeling them out through chemical and electtical sensors, or just digging for them.

MOUTHING OFF

One thing you can see is how bony fish body and mouth shapes fit their lifestyles, as diverse as the hard beaks of parrotfishes and the pointed snouts of butterflyfishes.

Many planktivores and piscivores have “protrusible” mouths that let them open wider and gain an edge in proximity to their prey. Fishes that spend their time grubbing in the sand for little invertebrates are likely to have “inferior” mouths, angled downward to facilitate their hunt. Fishes that lie quietly on the seabottom waiting to ambush prey passing above are likely to have “superior” mouths, angled upward to support their hunting technique.

WHO DOES WHAT, & WHEN

How Fish Feed 1. Daytime Grazers (Diurnal Feeding)

• Herbivores graze on algae and, conceivably, seagrasses. Herbivores include parrotfishes, many species of damselfishes, blennies, gobies, chubs, tangs and other surgeonfishes, and some filefishes and triggerfishes.

Throughout the day, princess, stoplight and other parrotfishes continually scrape algae from dead coral on the reef. Three-spot and dusky damselfishes cultivate little algae gardens all their own – and confront any fishes (or divers) that dare to come too close. Mobs of blue tangs rush frenetically around the reef grazing on algae.

• Planktivores focus on the microscopic stuff that floats along in the water currents, like eggs, larvae, copepods, dinoflagellates and the like. Planktivores include bicolor damselfishes and many other species of damselfishes, cardinalfishes, blue and brown chromis, creole wrasses, boga, blackbar soldierfish, jawfishes, garden eels, butterflyfishes and some squirrelfishes and triggerfishes.

Blue and brown chromis hover above the reef, facing into the current, vacuuming in zooplankton drifting along with the passing waters. Creole wrasses and boga stream along the reef in great columns, like commuters on a freeway, acquiring zooplankton as they advance.

Jawfishes and garden eels take less mobile approach. Extending themselves out of burrows in the sediments, they face into the current and sweep in zooplankton as it passes by.

Whale sharks and manta rays are planktivores writ large, relying on the “ram feeding” technique of swimming at speed with their mouths wide open to take in whatever morsels are in the water they are moving through.

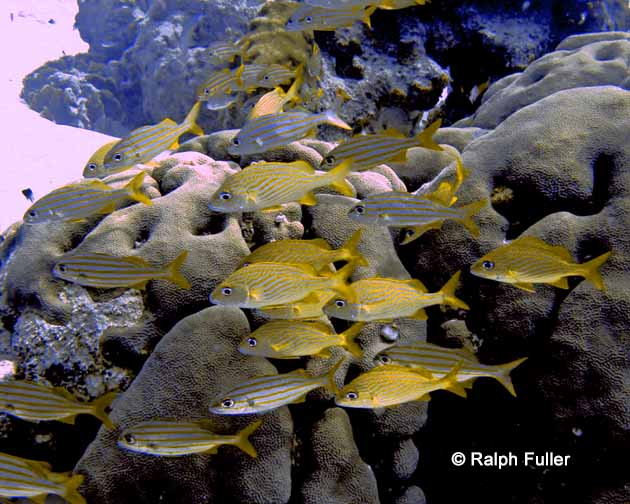

• Invertebrate-eating carnivores search their surroundings – often in seafloor sediments – for tiny mollusks, copepods, crabs, worms and the like. Invertebrate feeders include some species of angelfishes, butterflyfishes, blennies, cardinalfishes, squirrelfishes, cowfishes, some filefishes, flounders, grunts, some hamlets, most moray eels, and adult bluehead and yellowhead wrasses.

Bottomfeeding species like trunkfishes and triggerfishes are among that puff jets of water into the sediment to reveal juicy morsels – fracking, fish-style. Stingrays flap their broad pectoral fins to stir up the sand and uncover food. Goatfishes use chemosensitive barbels to search out the scents of worms, clams, crustaceans or whatever hidden in there. When they detect something edible, they plunge their snouts right into the sediment. Eagle rays use senses of smell vision, hearing and electroreception to detect prey, then plunge their shovels-shaped snouts into the sands.

Butterflyfishes and Moorish idols pluck coral polyps and anything else they can right out of the reef and tube blennies that both grab passing plankton and dart out to capture tiny bottom-dwelling crustaceans.

• Detritus feeders include fishes that earn at least part of their livings combing the sediments to scarf up algae, bacteria and other decayed organic matter. White mullets are one species often mentioned. Fishes like the honeycomb cowfish are usually described as invertebrate specialists but will consume detritus when convenient or necessary.

• Cleaners include sharknose and other gobies, juvenile parrotfishes and juvenile bluehead wrasses. Throughout the day, they provide client fishes with beneficial services and themselves with easy edibles by consuming parasites and dead skin cells.

• Piscivores include barracuda, groupers, coneys, graysbys and red hinds, jacks and some snappers, scorpionfishes, lizardfishes, frogfishes, tobaccofishes, and trumpetfishes. And most sharks, of course.

Through the day, barracuda and grouper remain vigilantly on station, hoping they’ll get lucky and detect a weak or lazy fish vulnerable to a strike. Scorpionfishes, lizardfishes and frogfishes lay in wait through the day, concealed by camouflage and sand, to lunge and nab unwary small victims as they pass by.

How Fish Feed 2. Between Day and Night & Night and Day (Crepuscular” Feeding)

• Piscivores like barracudas, snappers, jacks, mackerels, graysbys and the like mostly focus their hunting on the half-light hours at dusk and dawn. Prey fishes are on the move to find shelter, the lighting favors the eyesight of the hunter over the hunted, conditions are disorienting for the anxious prey.

• Moray eels begin to emerge from their hidey holes to prowl the bottom. Their primary targets are crustaceans and mollusks but they’ll grab any small fish they can take in the night.

How Fish Feed 3. The Night Shift (“Nocturnal Feeding”)

• Piscivores like jacks continue their fish-stalking (and indeed, jacks are on often on patrol throughout the day; they’re relentless).

• Invertebrate-eating hogfish and stingrays often can be spotted, working solo, mining the sandflats.

• Too many dive destinations seem to have a tarpon (named “Charlie”) that hangs out waiting to snatch up prey fishes revealed by diver’s lights.

• Grunts and other night-moochers gather in groups at the edge of the reefs where they’ve spent the day resting up. As they migrate to seagrass patches for a night of feasting on small mollusks and crustaceans, they dig their way across the sandflats.

• Squirrelfishes, cardinalfishes and big-eyes emerge from their hiding places under ledges and sponges to forage for invertebrates. Their large eyes help them see in the nights and their red colorations render them a protective dark gray in the darkness as they do their work.

• Similarly, fishes like spotted drums venture out from their secluded corners of the reef to forage.

Half to two-thirds of reef fish species are nocturnal, or night feeders, mostly invertebrate-feeders. The remainder earn their livings during the day or on the swing shift between darkness and light.

HOW FISH FEED 4. OMNIVORES, OPPORTUNISTS & CHANGING BEHAVIORS

• Fishes as diverse as horse-eye jacks, snappers and little sergeantfishes, can be described as omnivores – they’ll eat most anything from small fishes and crabs to shrimps, worms and jellies.

• And all fishes are likely to be opportunists. While they may have their preferences and lifestyles, those traits don’t deter them from pouncing on any easy meal that comes their way.

Even though their main work is searching the sediments for crustaceans and the like, I’ve watched spotted eels make short work of little fishes, sharptail eels methodically search hidey holes for fishy prey, and gray angelfishes casually gobble up little thimble jellies that suddenly appeared one day en masse.

• How fish feed changes for many specimens as they age. Juvenile bluehead wrasses, for example, widely and energetically engage in cleaning behaviors with larger fishes seeking grooming. But adults are likely to switch to seeking out invertebrates in the sediment.

Young bar jacks don’t clean but they do feed primarily on zooplankton in shallow waters. As one- or two-year-olds they’re more like to focus on invertebrates that can be stirred up from the sediments (often by stingrays they follow about). As adults, they’re likely to earn their livings with a varied diet of fish, shrimp, and other invertebrates.

HOW FISH FEED 5. THE VACUUM EFFECT – INHALING FOOD

Whether they scrape algae off coral, pluck out polyps from corallites, use powerful jaws to crush tiny gastropods found in the sand or snatch unsuspecting passing fishes in lightning ambushes, nearly all bony fishes share one common approach to food: They vacuum it in by simply opening their mouths.

Whatever the shape of their mouths, when they open their mouths they create a negative pressure that draws in water and anything that happens to be in it. As they close their jaws, the ingested water is flushed out through the gills. Some fishes like chromis do it by hovering in place, others like creole wrasses do it by swimming against the current, mouths continually in action. They look like they’re gulping in water. They are – and planktonic edibles.

Scientists have studied the hydrodynamics of this vacuum effect and confirmed that the suction effect is strongest directly in front of the mouth. It covers an area somewhat spherical in shape and decays rapidly with distance. Swimming during suction feeding narrows and lengthens the ingested volume. Not surprisingly suction feeding is most efficient when close to the prey.

Many fishes are able to protrude their mouths – that is, extend their upper jaws – in order to maximize their intake and get closer to the prey without moving physically. A fish called the slingjaw wrasse, found throughout the Indo-Pacific basin, can protrude its jaws as much as 65 percent of the length of its head.

HOW FISH FEED 6. PHARYNGEAL JAWS

At least when it comes to eating mollusk shells and chunks of reef calcium carbonate, fish have an advantage we humans lack. In addition to whatever is in their mouths, many types of bony fishes have additional pharyngeal jaws located at the back of the throat. Oral jaws capture food, pharyngeal jaws grind it up, pulverizing any shells or chunks or hard coral. These are passed through the digestive system for elimination. It’s true: Parrotfishes poop out sand, a very fine version of it that we lounge on at beautiful tropical beaches.

Most fishes’ pharyngeal teeth are fixed in the pharynx at the back of the throat. Moray eels have mobile pharyngeal jaws powered by muscles. After an eel has captured prey with its oral jaws, its pharyngeal jaws move forward, grasp the unfortunate victim and pull it down into the eel’s gullet.

One other pharyngeal factoid: The grunting sounds that give bluestriped grunts and their cousins their family name are produced by the pharyngeal jaws grinding together.

HOW FISH FEED 7. POINTY LITTLE TEETH. OR NOT

Fishes’ teeth reflect their lifestyles.Grazers like butterflyfishes and angelfishes have fine, hair-like teeth that serve their diets of algae, polyps, tubeworms, hydroids and sponges.

Wrasses have small, sharp, more protruding teeth that aid them in capturing invertebrate prey like small snails, crabs, worms and shrimps. Small, sharp teeth assist cleaners in carefully and precisely picking parasites and dead scales from their customers’ skins.

Sometimes, differences would seem subtle to us, as with two flatfishes: Flounders have well-developed teeth to facilitate diets of small fishes. Soles have more irregular teeth, reflecting their pursuit of bottom-dwelling invertebrates.

Despite their prominent mouths, trumpetfishes don’t have any teeth on their upper jaws and only tiny teeth on their lower jaws. Seahorses don’t have any teeth at all, and in fact, don’t have stomachs. Since they have poor digestive capabilities, they have to work on their diets of planktonic copepods almost constantly.

HOW FISH FEED 8. HUNTING PATTERNS

How fish feed on other fishes varies. First of all, fish like barracudas lack protrusible mouths and have to rely on good, old physical strikes to capture prey. By modern bony-fish standards, they have a primitive mouth loaded with large, sharp teeth.

I’ve watched barracudas hovering quietly in the shadow of boat hull during day dives, seemingly unaware of their surroundings – and, actually, vigilant for the main chance. Spotting a potential victim a good 15 or 20 yards away, they’ll suddenly contort into a “S” shape and shoot like a bullet toward their target. They’ll strike their victim and essentially bite it into two or more pieces. Then, circling back, they’ll feast on the severed sections.

A study of bluefin trevallys, a common jack in the Indo-Pacific basin, found these predators exhibit specific behaviors when on the prowl. They may swim steadily in the vicinity of other fishes without making any predatory moves – and without the potential prey reacting. When they’re preparing to pounce, they begin making zig-zag patterns at high speed, presumably alarming prospective victims.

Once within range, they zoom in to make their kill. But, immediately afterwards, surrounding prey fishes, noting the absence of pre-strike preparations, will again swim in proximity to the predator, ignoring its presence.

Some fishes team up to hunt – sometimes as mated pairs. Reef Fish Behavior cites mated harlequin basses stalking invertebrates like shrimps as an example. One distracts the victim in front while the other sneaks up behind it. Trumpetfishes often engage in “shadow hunting,” closely following a parrotfish or angel in order to hide its presence from potential prey.

Sometimes eels and other fishes join together to engage in “nuclear hunting.” The classic pattern is for a goldentail moray and a red hind or similar fish to coordinate an attack on a coralhead presumably known to contain small prey fishes. The eel rushes into one hole on one side, the hind stands guard on the other. One way or another, a fish desperate to escape will be cornered by one of the hunters.

I’ve watched this play out with sharptail eels and other fishes, although I’m not sure they were planned attacks so much as “sloppy seconds’ hunting.

HOW FISH FEED 9. SHARKS – ANOTHER STORY

Sharks have their mouths set back beneath overhanging snouts. With some 400 species, shark food preferences and feeding techniques range from the filter feeding of whale and basking sharks to the more familiar attack predation of great white, tiger and hammerhead sharks. They warrant an article all on their own.

It will have to suffice here to note that the hunting techniques of sharks who feast on fishy prey resemble the barracuda approach – striking, circling about and shaking and tearing their victims into chunks. Despite the well-known feature of constantly losing and replacing teeth, most piscatorial sharks swallow their food whole.

DEFENSIVE POSTURES

An important aspect of how fish feed is how other fish avoid becoming food. On the reef, both predators and prey are constantly vigilant. Schooling, stripes and colors help the hunted minimize risks. A large collection of bluestriped grunts moving slowly in a group makes it difficult for a predator to focus in on a specific victim. Those waiting barracudas are looking for a member who might be straying, not paying attention or perhaps indicating a weakness that hinders its escape movements.

And, those schools of striped grunts you often see resting next to a coralhead during the day are positioned there on purpose. The coral structure represents an obstacle to the trajectory of a barracuda trying to streak in to swoop up a fish.

And, obviously, some fishes just hide out, whether it be a spotted drum or cardinalfish hovering under a ledge, a jawfish or a garden eel retreating into its seafloor burrow, or a toadfish simply living in a hole.

PRINCIPAL SOURCES: Marine Biology, Peter Castro, Michael Huber; Reef Fish Behavior, Ned DeLoach; Watching Fishes, Roberta Wilson and James Q. Wilson; Reef Fish Identification Florida, Caribbean, Bahamas, Paul Humann, Ned DeLoach; Reef Fish Identification, Tropical Pacific, Gerald Allen, Roger Steene, Paul Humann, Ned DeLoach; Marine Life, Caribbean, Bahamas, Florida, Marty Snyderman & Clay Wiseman; Mouth Types, Surgeonfishes, Gobies, et.al., Florida Museum/University of Florida Museum of Natural History; Fish Mouth Types and Their Uses, The Spruce, Pets; Suction, Ram, and Biting: Deviations and Limitations to the Capture of Aquatic Prey, Integrative and Comparative Biology; Goatfishes, Waikiki Aquarium; Flounders, Grunts, Spotted Eagle Rays, et.al., Wikipedia.